At this point, the press behind Daft Punk’s latest album Random Access Memories borders on overkill. Yes, the release sounds totally different from everything else mainstream EDM these days – but that’s nearly entirely because the duo, along with collaborators Nile Rodgers and Giorgio Moroder, went for a back-to-basics approach and sound, while everyone else is looking for something different and digital and supposedly progressive.

At this point, the press behind Daft Punk’s latest album Random Access Memories borders on overkill. Yes, the release sounds totally different from everything else mainstream EDM these days – but that’s nearly entirely because the duo, along with collaborators Nile Rodgers and Giorgio Moroder, went for a back-to-basics approach and sound, while everyone else is looking for something different and digital and supposedly progressive.

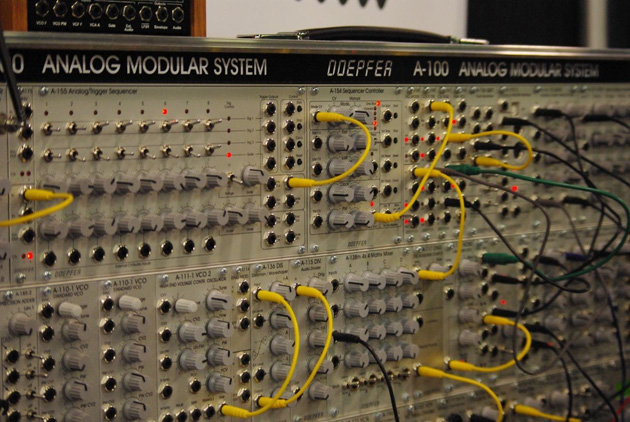

But the big reveal behind their select interviews has been the recording approach. Specifically, no computers were used. “We really felt that the computers are not really music instruments, and we were not able to express ourselves using a laptop,” they stated earlier. “We tried, but were not successful. It’s not really a judgment or criticism of any of the music today; rather trying to bring a different point of view and different alternative.”

Beyond the whole “we’re superior to other EDM producers because we don’t use computers” attitude, the French duo did highlight one growing concern with computer-created (and performed) electronic music – that everything sounds the same: “They’re not inviting you to challenge the systems themselves, or giving you the ability to showcase your personality, individuality. They’re making it as if it’s somehow easier to make the same music you hear on the radio. Then it creates a very vicious cycle: How can you challenge that when the system and the media are not challenging it in the first place?”

Even though you may dismiss Daft Punk, at this point, for being two pretentious tools, other long-time electronic dance music producers have raised this argument in recent months. The concern of analog synth sounds now easily accessible surfaced briefly in the BBC Radio 1 program we reviewed back in March, while both Ralph Falcon of Murk and Frank Lords of Secret Society delved into the topic at the 2013 Winter Music Conference.

During a panel discussion when the conversation veered toward new producers appropriating new sounds but doing it digitally rather than with analog equipment, Falcon stated, “The sound quality

Lords later followed up that statement with: “There’s nothing like the dirt in analog. I don’t think you can really pull that out of a digital plug-in.”

Is Analog Really Better?

As a 2011 CNET piece by Steve Guttenberg points out, the digital versus analog debate has perpetuated for about 30 years, with, as the author points out, some listeners favoring analog’s distortion and scorning the supposed coldness of digital. Guttenberg, on the other hand, isn’t speaking specifically about electronic music technology – rather, the vinyl versus CD debate. However, he points out, higher-resolution digital has shortened this gap.

Part of the analog versus digital debate, both in terms of medium and electronic music technology, is the natural sound of the former. In a 2005 Keyboard Magazine interview, Bob Moog, in speaking about the virtual simulation of vintage synthesizers, used an analogy comparing this debate to incandescent and fluorescent light: “What comes out of fluorescent light is a simulation of white, colorless light. When we look at sunlight or the light from an incandescent bulb, we get a continuous spectrum of colors and, to our eyes, this seems very natural. In fluorescent light, you don’t get a continuous spectrum of colors; you get discreet colors and they’re separated in funny ways. […] A fluorescent light may not produce those colors, so it distorts what we see to be the color of ink on the paper.”

But Moog soon turns back to the instruments themselves, claiming the distortion produced by analog simply can’t be duplicated by digital technology: “These very peculiar ways of distortion turn out to be very difficult to emulate with digital circuitry, and they’re impossible to duplicate exactly.”

He soon goes onto tell the interviewer: “These things are subtle, but the more you get into it and the more closely you listen, the more you become aware of this and the more it affects you as a musician, in the way the instrument responds to you and the way you respond to it.”

The responsiveness, or the way the equipment or instrument reacts to the player, gets lost with newer technology. Writer Steve Hillier, in article “Analogue VS Digital Synths” for Point Blank Online in August 2012, talks about a disconnect and a lack of interaction between the user and equipment, claiming the producer lets the gear do the work or relies on pre-created patches rather than making his own. “And with laptop producers having an attention span comparable to a gnat, this vast choice has turned us into hapless librarians, scanning through endless menus searching for something to excite us,” Hillier said. “We’re not getting our hands dirty but we are getting very bored.”

This empathy extends from the player-equipment interaction to how listeners perceive the sounds. Going back to Moog’s distortion argument, No Dough Music, in a piece titled “How Do You Get a Thick Analog Sound,” describes this facet as the factor distinctly connecting the listener – the aspect that creates a fan and ultimately results in record sales.

This empathy extends from the player-equipment interaction to how listeners perceive the sounds. Going back to Moog’s distortion argument, No Dough Music, in a piece titled “How Do You Get a Thick Analog Sound,” describes this facet as the factor distinctly connecting the listener – the aspect that creates a fan and ultimately results in record sales.

“For a producer working in today’s often overly clean, modern world, distortion offers you something that is sorely missing,” writer Matthew Sargeant said. “It doesn’t matter if you buy a pack of sounds that have been crafted to include this element or have splashed out on a foot pedal or even a vintage tape machine. Even the latest software emulation are getting useful on modern PCs. The most important thing is you are aware of this dimension and what it adds to your music; power, physicality, presence, warmth and it will sound more natural to your listeners so subconsciously they will find it easier to connect with your music.”

Just a Bunch of Debating Audiophiles

You know the ongoing debates in the electronic music world about which sub-subgenre a track falls into, be it robostep or brostep, progressive house or tech house, and so on and so on? The same can be said for the digital versus analog debate, be it for medium or where the sounds are being created.

In a How Stuff Works article, author Jonathan Strickland acknowledges that digital audio, because of compression, once sounded significantly inferior to analog, but analog to digital conversion has made leaps and bounds in this regards. As a result, the debate centers entirely around only subtle nuances at this point.

Strickland further highlights the conveniences digital technology has given music: particularly, that analog copies simply don’t last, while digital makes creating as many versions of a sound or recording possible.

Moog, to a certain extent, echoes this. Even though he spoke about the superiority, in regards to the finite, minute aspects of sound and music-making, in the 2005 Keyboard piece, the synth pioneer acknowledges that digital is far better for staying in a budget and learning how to use equipment.

Synthtopia, which regularly swerves back around to touch on this argument, stated in 2012 that the nostalgia for analog equipment makes producers and musicians overlook perfectly good digital synthesizers. As a result, the writer asserts, high-quality digital synthesizers have flown under the radar in recent years, as producers yearn for past decades.

From a production standpoint, musician Syncretia made in a blog entry, analog simply isn’t practical for today’s environment and technology. Although advocating for the individuality and character analog equipment gives, he explains that the older gear simply doesn’t integrate well with a modern DAW.

“With analog, there is a lot of stuff that comes in to play that you would not have had to think about before,” Syncretia wrote. “You will need a sound card that has a good audio in, it will have to be configured for this use, you might require the sound card to have a midi out (depending on your level of integration), you may need to have good playing skills, you will need quality cables (including midi and power cables and transformers – cables often break leaving you with a troubleshooting scenario), you will need space on your desk/rack for the synth, you will need to learn the peculiarities and quirks of the synth, and so on. This is not to mention that analog synths often break and go out of tune.”

With this degree of complexity, aiming for authenticity begins to appear like a time-consuming process, particularly when virtual simulations are easily accessible, cause fewer issues, and simply integrate better.

But in going back to Daft Punk’s assertions to the press, their process seems less forward-thinking (or simply moving backwards to go forwards) when you consider how they’ve recorded since the beginning, regardless of sample-heavy early works or the natural instrumentation of Random Access Memories. Revealed in a Time interview in May, Thomas Bangalter mentioned they started with reel-to-reel recording and, by Random Access Memories, moved to “hardware electronics and analog equipment” – computers have never been used.

In the scope of electronic music, regardless of whether you consider Random Access Memories innovative or regressive, or all other EDM tracks carbon copies because of digital technology, computers, and accessibility, the latter is here to stay, and virtual simulations of retro sounds are an adaptation.

“I don’t know if laptop performances are a necessary evolution, but it’s certainly where the music is headed,” producer Blockhead foreshadowed in a 2010 Wired article. “Everything is computer-based now. There’s really no room for analog in electronic music anymore, unless you’re freaking crazy old keyboards.”