Since 2012, we’ve been hearing that this EDM thing is about to reach a peak. Trend forecasters ended up wrong after festival attendance and record sales surged globally, with North America consuming a greater portion of the market.

2014, however, appears different. It’s not so much that all aspects have decreased, but rather that ticket sales for major U.S. festivals hit a plateau. Recent introductions to this side of the pond, such as TomorrowWorld, experienced slower reception, while stalwarts like the Ultra Music Festival continued to sell tickets up to when the event occurred.

While this may the point that EDM officially reaches a peak (we probably won’t be able to officially know until the end of the summer, however), electronic dance music history has a habit of going through the same motions over and over. The sounds and performers may change and evolve, but one thing’s for certain, after a style goes underground, experiences some mainstream success, and then gets adopted by pop artists, there are only really three ways to go: fade out as an old fad, evolve into something different, or experience a revival.

So in 15 years’ time, where do you think EDM will be?

Disco serves as a template for a subgenre’s evolution. Especially if you’re in the U.S., there’s a good chance you can remember the day in 1979 when disco officially “died” with Disco Demolition night in Chicago – or know someone who can at least talk about it.

However, beyond this isolated event, disco’s increasing presence that came up through the clubs, resulted in hits for a diverse group of artists ranging from KC and the Sunshine Band to Giorgio Moroder and Donna Summer, and spawned a mainstream sound adopted by pop artists, including Cher, Blondie, Rod Stewart, Elton John, and Diana Ross almost suddenly disappeared in the early 1980s. A handful had hits past this point, but historically, there are a few factors that, especially in the U.S., nearly obliterated disco from its Top 40 presence. One, listeners began to lean more toward musician-created songs, rather than those producer based. Two, country music began to see its presence grow. Three, decreased success for disco artists meant subgenre labels closed. Four, the subgenre became associated with promiscuity and drug use.

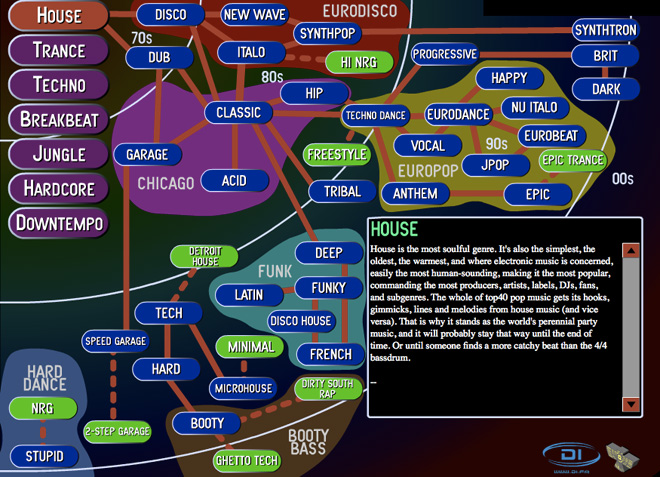

Although disco died on a mainstream level after 1980, really only continuing in pure form as Euro Disco on the other side of the Atlantic through the middle part of the decade, it serves as the prototype for what can happen to a subgenre. Yes, the sounds may ultimately become antiquated, but disco’s rhythm and melodies took a darker turn – and really becoming the source for a great Diaspora of electronic subgenres, such as house, techno, synthpop, Italo disco, dance pop, and Eurodance.

Much of the ‘80s subgenres followed such an arc. Synthpop – really, an amalgamation of disco and ‘70s electronic music from Kraftwerk and Brian Eno – reached its heyday by the late ‘80s, only to find itself replaced in the U.S. by grunge in the early ‘90s; artists continued to experience minimal success by either adapting to the ‘90s alternative rock climate (think Depeche Mode’s 1994 release Songs of Faith and Devotion) or experimenting (like the Pet Shop Boys trying out a Latin dance club sound in 1995’s Bilingual, mimicking the sounds of New York club culture on Nightlife, and then going soft and guitar-based with 2002’s Release).

Similarly, as we detailed recently with a piece on Freestyle, a uniform sound that didn’t change with the times and didn’t fit in with urban or dance music radio formats eventually meant the end.

But this ascend-and-fall structure isn’t something exclusive to artists finding success in the U.S. Although synthpop artists tended to have longer careers in Europe (for instance, you’ll never see New Order receiving a lifetime achievement award over here), U.K. Garage was “the thing” for a few years, before it evolved into something else.

U.K. Garage follows a similar arc, staying underground for a few years before artists like Craig David, Oxide & Neutrino, and Artful Dodger having singles rank high on the U.K. Singles Chart. But Garage, somewhat similar to what mainstream EDM producers do these days, borrowed from pop music genres, with vocals from soul, rap, reggae, and R&B artists. As a result, Timbaland taking on the Garage style might be considered its mainstream peak.

However, for those that know their bass music history, garage might have worn out its underground cred, but its sounds – much like disco on synthpop, house, and techno – became the roots for grime and dubstep.

However, what synthpop, U.K. Garage, and even freestyle all have experienced, in 20 years since losing mainstream popularity, is a revival. For synthpop, this was the late ‘00s, with artists like La Roux, Frankmusik, and Owl City having hits in the U.S. and Europe; some even consider mid-‘90s electronica an offshoot of synthpop’s approach. Freestyle’s now having a moment, especially with Pitbull working with older performers like Lisa Lisa and Stevie B. And while many may say Disclosure’s doing a Garage revival, particularly with the vocalists the duo collaborates with, Future Garage has been a return to form, of sorts, with producers revisiting the older sounds while keeping a modern sound.

Still, a “part two” for any subgenre is a rare thing, and there are others that simply become something else. Eurodance perfectly exemplifies this. Essentially the amalgamation of everything moderately underground in the ‘80s – some techno beats, house melodies and vocals, synthpop rhythms, and trance arpeggios – Eurodance found the greatest mainstream acceptance until Electronica came along. At the time, Eurodance tracks found success in Europe, North and South Americas, and even Australia, but a formulaic approach ultimately made listeners want something different in all senses of the word by the early 2000s.

Although Eurodance still exists in some form, with Basshunter and Cascada still putting out releases, trance producers absorbed its style. As a result, the 2000s transitioned from instrumental-based trance tracks to those with the vocals front and center. Simply trace Armin Van Buuren’s or Tiesto’s series of hits as examples of such evolution.

Although EDM, or specifically hit-making progressive house, is both an offshoot of Eurodance and an amalgamation of everything before it (seriously, trouse with a bit of dubstep and a Nile Rogers appearance doesn’t seem that far off), could it simply be a sound that’s wearing out its welcome? After all, complaints about EDM – especially that it’s producer based and associated with promiscuity and drug use – reflect early ‘80s attitudes toward disco. But even then, once listeners move on to something guitar-based (if it can happen to disco and synthpop, why not EDM?), will this subgenre be something producers revisit in another 15 years, or another chapter of dance music history, à la Eurodance, that officially ends?