If you had already thought EDM got as corporate as it could possibly get, from festival sponsors to Live Nation buying up Insomniac, guess again.

Early in March, Forbes writer Jesse Lawrence recommended investing in EDM stock, specifically SFX Entertainment, which went public last year.

Lawrence lists multiple reasons investors ought to consider EDM: ticket prices continue to rise, the U.S. has seven major EDM festivals, the genre has a global market, and the Ultra Music Festival, which starts off the concert season, is estimated to generate $200 million.

But there are two ways Lawrence is misguided: one, SFX Entertainment’s NASDAQ stock has faltered, in spite of promising beginnings, and two, the most stable music stocks outlast any trend. Could SFX Entertainment – a company that’s just three years old – ever end up having the same history, and reliability on the stock market, as Sony or even Amazon.com?

The Year EDM Officially Went Corporate

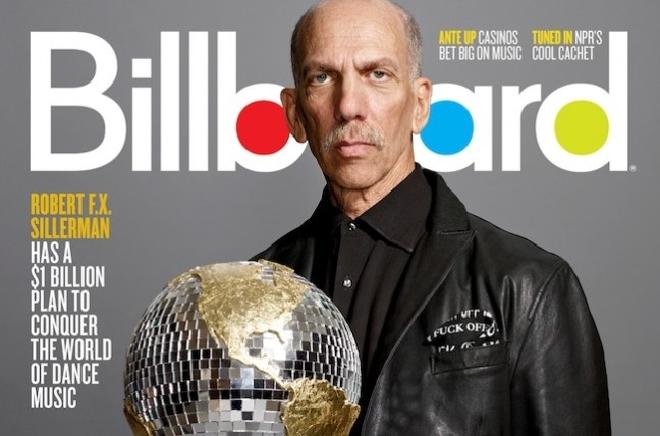

The growing wave toward the shores of corporatization began with David Guetta collaborating with the Black Eyed Peas in 2009. Then, with festival attendance soaring stateside, 2012 meant Live Nation Entertainment spotted another goldmine, eventually bidding for and acquiring Insomniac, the company behind mega-festival Electric Daisy Carnival. By 2013, SFX Entertainment took a similar approach but one that was EDM exclusive: The company now operates Beatport (and was responsible for layoffs toward the end of 2013), Donnie Disco Presents, and Made Event, and is looking to take on ID&T, the promoters behind TomorrowLand.

Becoming an EDM conglomerate hasn’t been enough for SFX, however, and last year, the company filed an initial public offering with $260 million – larger than expected to be raised. But the hype of an EDM stock appeared short lived. In just one day, SFXE dropped as far as 16 percent from its initial $13 dollar per share. The stock eventually settled at $11.89 – a decrease of 8.54 percent.

Robert F.X. Sillerman echoed similar statements with SFX’s IPO; mainly, fan engagement and festival growth are great enough forces to sway investors. But the company made one clear declaration: that stock depends on how well the trend does. “While interest in electronic music has increased significantly over the past few years, this increase in interest may not continue,” the statement read, “and it is possible that the public will not sustain its current level of interest in electronic music. If either were to happen, the demand for, and interest in EMC festivals, events and venues and our online properties could fail to meet our expectations or even decline. This would have a material adverse effect on our business and financial results.”

Investors ought to keep in mind that during the second half of 2013, SFX experienced $44.6 million in losses on revenue of $37.5 million.

Looking at the Music Industry Overall

In recent years, music publishing companies have looked toward the stock market model to promote songs and ultimately get funding for artists. Tune Rights starting taking this approach in 2011, and then TweeIX took it to another level in 2013 by marketing to and getting potential investors to fund artists based on their songs.

While this business model doesn’t rely on the traditional stock market and is too new to determine its success, the greatest consistency on the OTC, NYSE, NASDAQ, and S&P 500 appears to correlate with a product that transcends genre and trends.

For instance, the most reliable music industry-related stocks are Sirius XM Radio, Inc.; Vivendi Soci, an international multimedia and digital product provider; Live Nation Entertainment; Pandora; Sony; Best Buy; Virgin Media; Clear Wire; Time Warner; and Amazon.com. As you can see, the majority of these offerings lean toward major labels and concert promoters with decades of history and that represent artists of multiple genres. The next step down appears to be retailers, brick-and-mortar or online, that continue to adapt to the marketplace in some way or form. And third are a group of radio stations that, outside of terrestrial signals, continue to fill a niche for users wanting more genre- or listener-specific content.

Although Live Nation has a growing role in the mainstream electronic dance music world, its existence hardly depends on Electric Daisy Carnival. Should attendance drop at the largest EDM festival in the United States, Live Nation has the history and clout to attach itself to another trend without seeing its stock prices significantly tumble.

As much as SFX Entertainment is trying to play corporate, its lack of history and genre-specific model – keep in mind, too, a genre that shot to the top of the North American charts in a very brief time – make it unstable beyond the IPO.

Music stocks, as well, fall within the vast scope of out-of-home entertainment – a luxury that gets cut of out of most consumers’ budgets once the economy falls. Billboard pointed this out in 2011, when economists feared a double-dip recession.

As the music magazine detailed, music stocks inevitably get hit when the economy falls, as consumer spending and Dow Jones figures factor into the stock price. Because even the most successful music stocks depend on consumers buying tickets and albums, no investment is truly dependable.

On the other hand, stocks from internet-based companies, such as Pandora, are considered less reliable, and as Billboard notes, the lack of history for dot-coms, particularly those based on a trend like internet radio, resulted in a 22.57-percent drop in 2011.

Taking all factors into account, SFX Entertainment – and any other EDM industry promoter or label looking to go public – falls within the crosshairs of stock market unreliability: The entire business model depends on a trend and its rise, even with physical forms like festivals, is partially attributed to the internet.

As much as getting on the stock market embodies everything corporate and selling out for dance music, there’s something far more insidious than a promoter or label taking the ultra-mainstream path: That is, leading investors who have no or limited knowledge of dance music to think that buying up stock is a long-lasting, profitable endeavor.

The fact of the matter is, dance music never learns from its mistakes, but one thing’s for certain: Trends die, be it electronica passing, trance losing relevance, or Tony Wilson closing the Hacienda club. At some point, EDM will reach its peak and fall, going back to the underground or in a new direction; will investors counting on promoters-gone-public still be there?