When my set was over, a young, aspiring DJ pulled me aside intent on educating me. He claimed that only as an established “insider” was I permitted to mix and match between genres as I pleased. Clearly, I hadn’t got the memo. Despite ten-plus years of DJing under my belt, apparently, I was not considered an “insider”. Needless to say I laughed in his face, then bought him a beer to explain the following.

What he was referring to is a concept I like to call ‘Genrefication’. This is a belief in the practice of genre restriction encouraged by the so-called purists on the ‘scene’, and drilled into the minds of new young talent hoping to break in. These ‘purists’ advocate for a linear and predictable sound that is easily identified as ‘cool’ or ‘underground’ due to its perceived distance from pop culture; or what is familiar to the ‘purists’’ self-imposed nemesis: the masses. Ironically, as Dick Hebdige, the author of Subculture: The Meaning of Style, points out, subcultures indirectly challenge the power of the dominant norm through style. “The objections are lodged, the contradictions displayed at the profoundly superficial level of appearances…” In this case, the “appearances” are auditory, as opposed to visual. When you make connections between different genres, many of which are more accessible or recognizable, you also connect their associated subcultures and you erode the fragile constructions of any single group. This is where content challenges form.

What he was referring to is a concept I like to call ‘Genrefication’. This is a belief in the practice of genre restriction encouraged by the so-called purists on the ‘scene’, and drilled into the minds of new young talent hoping to break in. These ‘purists’ advocate for a linear and predictable sound that is easily identified as ‘cool’ or ‘underground’ due to its perceived distance from pop culture; or what is familiar to the ‘purists’’ self-imposed nemesis: the masses. Ironically, as Dick Hebdige, the author of Subculture: The Meaning of Style, points out, subcultures indirectly challenge the power of the dominant norm through style. “The objections are lodged, the contradictions displayed at the profoundly superficial level of appearances…” In this case, the “appearances” are auditory, as opposed to visual. When you make connections between different genres, many of which are more accessible or recognizable, you also connect their associated subcultures and you erode the fragile constructions of any single group. This is where content challenges form.

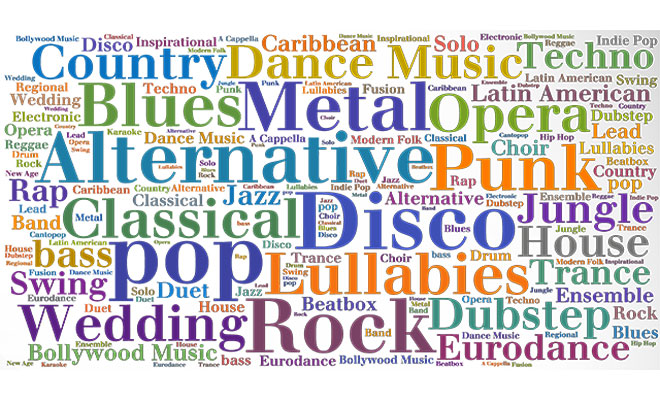

It is no secret that electronic music is the most incestuous music around. From Karlheinz Stockhausen to Kraftwerk to Frankie Knuckles to Autechre, new artists directly build on, borrow and sometimes steal from their counterparts to generate new sounds, songs and genres. All of them are separated by fewer than six degrees. Let’s review. Disco gave us House and Hip Hop, Hip Hop gave us Electro, and Electro with House gave us Techno; Techno was stripped down to make Minimal, and Minimal and House gave us Tech House and then, and then, and then some. But don’t take my word for it, just check out Ishkur’s Guide to Electronic Music, get lost in SyncLost; a multi- user installation for immersion in the history of electronic music, or warp your brain reading Joseph Kelly’s article “Deep Structure of Techno”. Wikipedia lists 18 genres, 187 subgenres and 27 sub-subgenres of electronic music.

Their connections form a spider web or, more aptly, a rhizome of intimate connections that are shored up by advances in affordable technology and the continuous cross-pollination by innovative young producers and DJs. As a result, the music’s evolution and configurable nature reflect a postmodern condition. Like so many other things – art, media, design, architecture- it is being remixed, recycled, reused, reinterpreted, cut up, and filtered. But by connecting the dots we expose these linkages and chart an intimate musical history. By leaving the comfort zone of a single genre, we can look to a future where these basic categorizations may become archaic or even altogether useless.

Their connections form a spider web or, more aptly, a rhizome of intimate connections that are shored up by advances in affordable technology and the continuous cross-pollination by innovative young producers and DJs. As a result, the music’s evolution and configurable nature reflect a postmodern condition. Like so many other things – art, media, design, architecture- it is being remixed, recycled, reused, reinterpreted, cut up, and filtered. But by connecting the dots we expose these linkages and chart an intimate musical history. By leaving the comfort zone of a single genre, we can look to a future where these basic categorizations may become archaic or even altogether useless.

Regardless of whether you stick with one genre, or decide to cram as many as you can into your DJ set, it’s more important to focus on sharing the music you enjoy and stop fabricating any sort of close-minded musical inertia.

“The joy of true creativity is the exploration of the unpredictable. At the point that creative energy becomes fully predictable and formularized, the flickering spirit of the divine is extinguished and camouflaged conservatism takes over, fed by the desire of many to be safe within the familiar.” -Genesis P-Orridge

“It’s all called techno or dance music now, ‘cause it’s all electronic music created with technological equipment. Maybe that should be the only name, “dance music”, because everybody has a different vision of what Techno is now.” – Kevin Saunderson

For additional reading check out:

http://ensemble.va.com.au/enslogic/text/smn_lct08.htm