Mixed In Key

You’ve been playing for a while and, let’s not be modest, you’re pretty damn good. Your timing is tight and you can work those effects like nobody’s business. You’re getting to the point that you even have your own sound, but you’re not a trained musician. And while you can kind of hear when two songs work together harmonically, you’re buggered if you know why – or more importantly – how you can use it to really make your sets sing. If only there were some kind of tool you could use instead of spending twelve years learning about Liszt and Chopin. If only…

Enter Mixed In Key. I’m going to come right out and say it: this is one of the most important tools in my bag, and one that gets a workout every single time I buy a track. The premise is simple – it analyses your tracks and inserts the key information into the ID3 tags. That’s it, really. I mean, it’s wrapped up in some more handy bits and pieces like the Camelot notation we’ll come back to, but Mixed In Key exists solely to identify the keys of your tracks so you can mix harmonically like David Guetta, Hernan Cattaneo, Dubfire, Paul Oakenfold. The list of endorsees for this program reads like an honour roll from the DJ Hall of Fame.

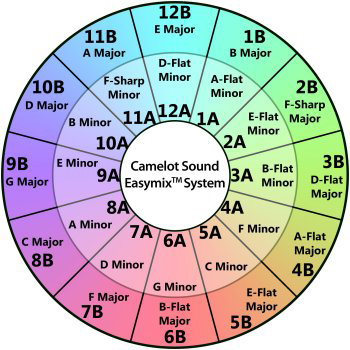

Camelot Sound Easymix System

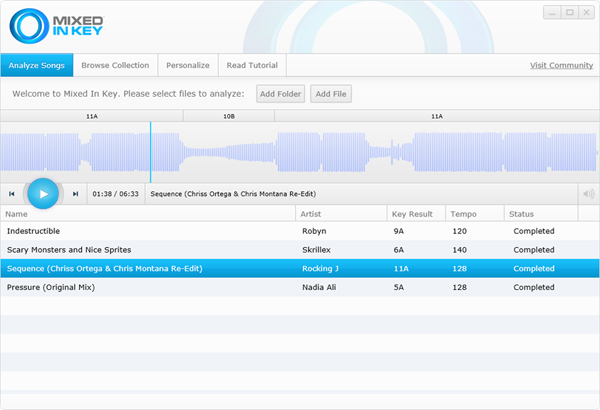

The program itself is simple, at least from the user’s point of view. The first page is where you analyse your songs. Browse and add whole folders or single tracks and hit go; that’s it. It’s nice and fast too, although if you’re doing your whole library that first time, you might want to leave it running overnight. You have the choice to have the BPMs reanalysed too, and there are a few different choices as to if and how the new information is appended to the filename.

Mixed In Key 5 analysis with two keys

The second page lets you browse your collection, play tracks and sort them according to the key, as well as sorting and saving playlists into folders, and exporting each as a CSV file. My OCD is loving it!

Page three is where you’ll find instructions on how to use the new tags with Live, iTunes, Rekordbox, SSL, ITCH and Traktor, as well as a few settings for the way tempos are displayed, and how the music player behaves. It’s also where you’ll decide the default notation convention: sharps, flats or Camelot. Camelot is the easy way out and it’s really a great, simple way of learning the keys in the first place. It works like this: major and minor keys are placed in concentric circles, like a clockface. The outer ring is B Major and the inner ring is minor, so one o’clock is either A flat minor or G sharp minor, depending on your preference. Or, they’re 1B and 1A respectively – that’s Camelot notation – and by sticking to jumps of one “hour” at a time, you can be assured that your tracks will work together. It doesn’t matter whether or not you know that C minor and F minor work well together, because at a glance you can see that they’re adjacent in the ring and so you’re safe, whatever the proper names might be.

Mixed In Key with Camelot

It’s great stuff – simple enough for anyone to use and powerful enough to have real impact on your mixing. It’s also supported by an active community who seems to love nothing more than bending the rules and exploring the musical implications of the various mathematical relationships found around the clock, and working them into their sets. And at just under $60, it’s a steal – in Australia, that’d get you a one hour lesson with some musty Stravinsky aficionado who would probably insist that you can’t hear the music until you’ve played so many scales that you bleed from your eyeballs.

Don’t bother. Shell out the sixty bucks and take the easy road.